A little over 10 years ago, Matt Leacock’s Pandemic popularized the cooperative board game. In 2020 world events helped to draw some more attention to the game’s theme. More importantly, though, it showed that cooperation at the gaming table suffered from similar road blocks as cooperation on a state level does. With Daybreak (re-named “E-Mission” in Germany) Matt Leacock and Matteo Menapace combine the design experience of the last decade, with the carefully researched background of the climate crisis. The resulting game deserves to be placed next to the cooperative classic.

Daybreak frames its in-game interaction as the fight against global warming. As a representative or personification of global actors, we try to reduce our CO2 emissions as well as switch to a less harmful, i.e. “greener”, way of life. The theme is highly topical, and as such adds a sense of gravitas to the game. It’s tempting to reach for the label of “serious game” when trying to describe Daybreak. But in doing so, it unduly limits the game’s impact.

Because the term “serious game” often describes a game, that aims to illustrate its theme and make it more approachable to its audience. It describes games, that aim to make players interested in their theme. In some cases, to even educate players about it. In other words, they are games that function as museum exhibitions. You will find QR codes on almost all cards in the game, which lead to a page that both explain the card’s rule as well as the scientific background of its effect. So, if you’ve ever wondered what the point of a “Community Solar Project” was, you are given ways to educate yourself after the game. If encouraging players this way is what you consider board games’ greatest strength, and the thing that makes them culturally relevant, you will find much to be excited about in Daybreak.

Personally, I consider this perspective on board games provincial. It’s akin to praising film for allowing for documentaries. Or elevating literature to cultural relevance, because they can also relay actual historical contexts. Yes, these media are capable of doing that. And yes, board games can also function like at-home art exhibitions and educate their players on certain topics, or even explain things to them, that they were unfamiliar with. This medium is without a doubt capable of such things. But considering this as the medium’s only potential to have cultural relevance, betrays a deeply backward understanding of culture.

Because if all Daybreak did was use cooperative gameplay to educate its players about global warming, it would be an unfathomably dull affair. Luckily, Daybreak is more than over-bearing didacticism. It develops – precisely because it never loses sight of its nature as a game – a fascinating and deeply immersive appeal for its players.

Daybreak is a game about the failure of the individual and the triumph of the community. It’s a game that presents us with seemingly unsolvable problems at first. And it’s a game that hammers home the idea – through repeated failure if necessary – that global problems can only be tackled through intense cooperation. This is similar to an idea that was present in Pandemic: cooperation is the end point, not the means. But this time this insight is not hard-wired into the rules. It was practically impossible to play Pandemic, without talking to each other and agree on a shared approach to winning the game. In Daybreak this realization emerges naturally as you play. Provided players are open to adopting to new information. After all lamenting the capriciousness of fate is an easy way to distract from your own shortcomings.

If you play the game with a myopic focus on your own player tableau, the game tends to hit the wall by round 3. Your personal achievements evaporate meaninglessly, unless you purposefully coordinate how to slow down the escalating climate change.

That is why the most impressive thing about Daybreak isn’t the careful research, that went into each cad. It’s also not the science-based and easy to follow depiction of our eco system’s interconnections (including simplifications and abstractions made for sake of playability, as the rulebook points out). What’s impressive is the need to work together is a consequence of the game’s challenge itself, as opposed to a rules inevitability.

All this makes Daybreak less of a “serious game” and instead a “political game”. It’s a game that purposefully approaches its theme to suggest an intended realization on the players’ side. You could, of course, argue that every game is political. It’s a cultural artefact and so it’s beholden to reproduce specific cultural narratives, whether knowingly or unknowingly. That is why Brass Birmingham is probably the best propaganda game about capitalism. Nowhere else is it more fun to profit off of the work of unseen masses of workers, so you can spent it all on fame and fortune and boosting your self-worth.

Ingeniously, Daybreak doesn’t draw its enjoyment from working with others. Its biggest appeals lies in creating, developing and improving your own projects. Reducing your population’s CO2 emissions by cleverly activating cards, improving them or replacing them with others, is as easy to do as it is rewarding. You are constantly bringing about change, and every time it feels like an improvement. But if you don’t pay attention to other players’ progress, your chances of success are unlikely to improve. You will depend on the luck of the card draw, and likely lose the game a short time later.

You might criticize that climate catastrophe is a serious and pressing issue, and not the right fit for an entertaining game. Perhaps the positive experience of playing Daybreak trivializes the bleakness of where we are right now. The optimism we feel with this game may suggest that things aren’t as urgent as they actually are. Although some players might also look at the game’s challenging difficulty and deduce that we might be even worse off in reality.

I hesitate to agree with those points. Climate pessimism is, regardless of any facts it might be in reference to, neither worthwhile nor expedient. Even if the situation were hopeless (but not serious), a game that only serves to make people despair would be more than just worthy of serious criticism. It doesn’t matter if Daybreak’s belief in the efficacy of global cooperation is realistic; it is imperative. And it is this reminder of universal values and ideals, that emerges as we play, that puts Daybreak far above games that want to teach players about their theme.

Still, when viewed critically, it becomes apparent that certain factors aren’t explicitly addressed in the game’s theme. Large scale industries and the economic systems that keep them afloat are merely woven into the game’s mechanisms. The CO2 emissions you are responsible for in the game are split into industry, agriculture, transportation, buildings, etc. It’s only when you start using cards (projects) to reduce them, you’ll note that they have names like Universal Public Transport, Fossil Fuel Nationalization, Walkable Cities or Heat Pumps. None of which are talking points of so-called business oriented policies. In Daybreak we predominantly have to deal with unpredictable crises of an out-of-control eco-system. The causes for this, like the fact that 100 internationally acting companies are responsible for 71% of CO2 emissions is likely only known to players who are familiar with the theme. But if Daybreak needed a tangible antagonist, the untamed capitalism of the super-rich would certainly be first choice. As it stands the pressure players do feel is packaged as energy demands of their population. If they can not be met, it leads to Communities in Crisis, which leads to disadvantages in the game which in turn hastens defeat.

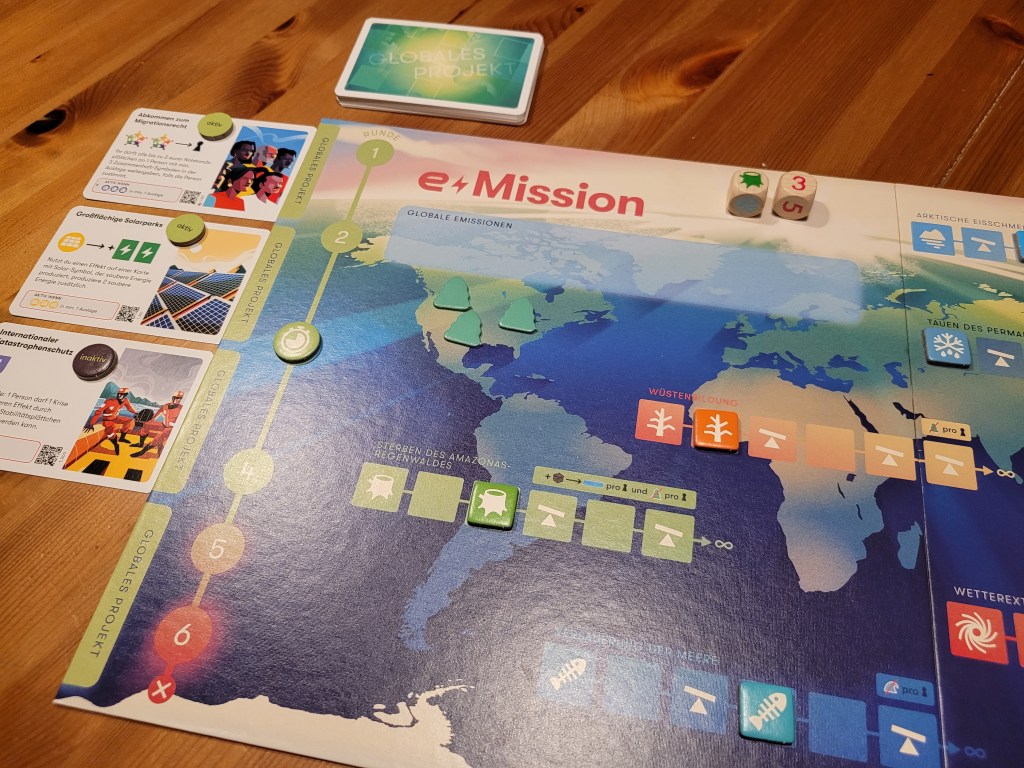

It’s at this point that the German edition of Daybreak (called “E-Mission”) unintentionally adds a level of performance art to the game. German publisher Schmidt Spiele chose not to produce the game in China, but opted for local production in Germany instead. This naturally led to some changes for the game. The game board is smaller. The rulebook is shortened by a number of pages and the tokens are no longer wood, but thick cardboard instead. In addition to that, the player tableaus are significantly thinner. These cost-cutting measures invariably affect the experience.

This is most apparent in the rulebook, which omits some layout decisions and texts of the English original. Those helped make the game more approachable and emphasized a positive and optimistic starting note. It’s no coincidence that some English language reviewers consider Daybreak almost too optimistic. It’s small details like these, that can have a large impact in how games are perceived. The change to cardboard tokens makes the game’s tactility feel a little more ordinary. The thinner player tableaus also add to the feeling that this isn’t as high quality a production as we are used from other games in this price range.

But it’s these whiny nitpicks that E-Mission uses to ask ourselves the question that Daybreak only posits sub-textually: are we willing to let go of even these small luxuries for the sake of the environment? For the longest time, gamers smugly referred to games as a luxury they “treat themselves” to. But maybe this is exactly the problem? Maybe equating games to luxury is the reason we expect the most ostentatious and expensive game production that “our” money can buy? Maybe it’s the reason why we still rave “how much game we get for our money”, instead of highlighting the actual experience the game provides? Maybe we have to separate games from luxury, so we stop measuring their value in how eye-catching and blinged out the components are. Because a game’s price shouldn’t be a measure of how much high quality and elaborately produced

content the game comes with. It should be seen as what it actually is: an entrance fee for an experience. The price point of a game in actuality only expresses the publisher’s target audience for their product.

But when we spread “E-Mission” out on the table, we’re forced to choose which side of the climate discussion we want to take as board gamers. Do we want to be the group, that doesn’t want to do without opulently produced games, and expects a great productions at a price of 80€ regardless of what CO2 emissions we condone with it? Or can we compromise and accept a game that is produced as it is? Is a thinner tableau, a lack of wooden tokens and a shortened rulebook something we can live with? Or do we pass on this game (or board games as a whole, if they don’t meet the luxurious standards we believe we are entitled to at this price?

Regardless of how you want to answer these questions, Daybreak is a game that motivates with impressive effectiveness due to its stellar design. Even after repeated defeats, it manages to invoke ambition and optimism, that the next attempt will surely be successful. There’s always the option of cooperating more closely, more focused. In light of its theme Daybreak offers something more valuable then simple interest in the scientific background: it makes us feel that climate change is a tangible task, that we can tackle, even if it is enormously challenging. This makes Daybreak not just an exceptional game, but one that is also culturally relevant in the strongest terms.

3 thoughts on “Game Night Verdicts #86 – Daybreak”