War & Write II is the follow-up to Mini WWII, which I hold in quite high esteem. That game presented an abstracted, strategic perspective on war in an unobtrusive manner. But in doing so, it involuntarily revealed the dearth of humanity inherent in that perspective. The game did not distinguish between troop sizes, nor did it introduce dice to simulate fog of war. It was a rigidly structured game in which we solved a logistical challenge. We invaded countries, sustained our presence on the board and researched technologies, to gain a tactical advantage. The number of casualties such actions would incur in the real world, were no consideration in Mini WWII. They only existed, if at all, as a crude comment at the table. I was impressed by the game because I felt that this pitiless reduction to small numbers felt refreshingly honest. The ugliest face of war belonged to what Germans call “Schreibtischtäter”: the guy making unconscionable decisions from the safety and comfort of his desk. That was the perspective we were given in Mini WWII.

Both presentation and experience of War & Write II stands in the starkest possible contrast to that. While it’s still arguably a game about a logistical challenge (i.e. getting our troops to a specific space on the board at a certain time), we approach it by anticipating the plans of our opponents and attempt to foil them. We’re trying to plot our own troop movements around that of the enemy, in the hopes of winning battles elsewhere through brute numerical superiority.

War & Write II doesn’t build on the game concept of the popular roll&write or flip&write genre. Instead it uses pencil and paper as its means to note movement orders on your player sheet. The fact that his harkens back to early days of wargames might not be immediately obvious, but shows that these two genres aren’t that far apart.

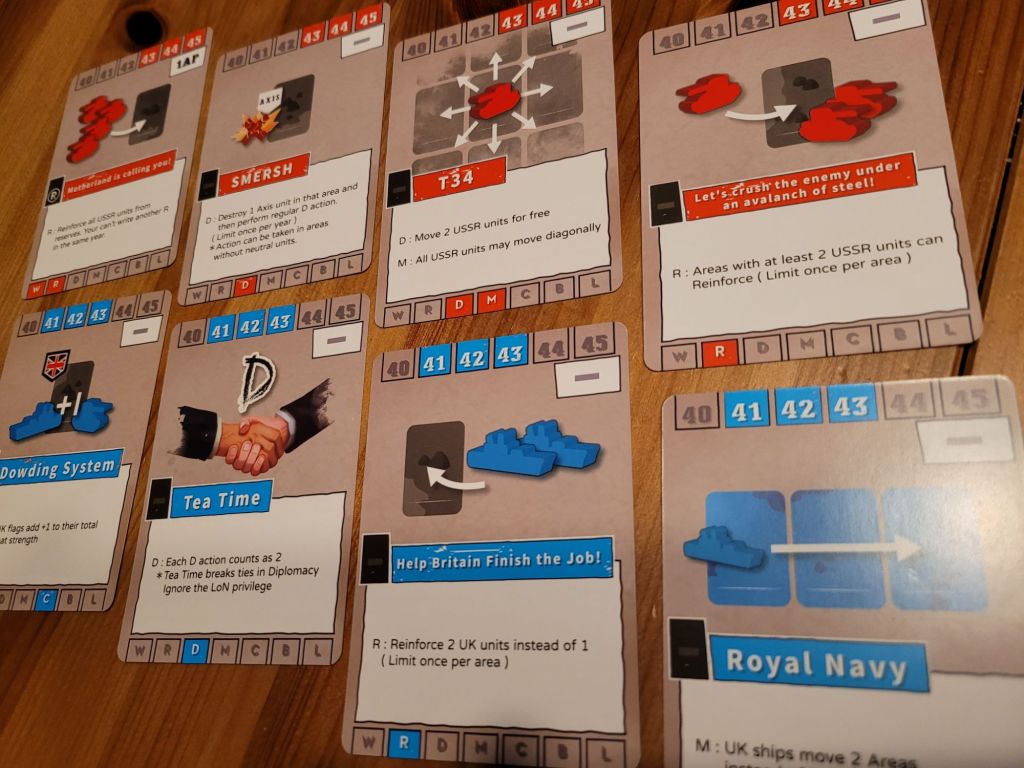

Every game of War & Write II is played over 6 rounds. In each round you have to move your tokens to a specific location on the board to score points. The sum of these points will determine which side is in the lead at the end of a round. If your troops meet enemy troops, a battle ensues. Simple majority is enough to remove all enemy tokens in that space off the board. In some rounds certain board spaces are of particular importance. As having a token on them means additional points or additional tokens to command. Getting new tokens otherwise costs one of the scant few orders you have each round. At the same time, you have to keep individual special abilities in mind, which are available during specific rounds. That’s why it helps that in the usual setup, you have an ally to confer with against the enemy team. The open exchange is as much part of the design, as it is part of the experience. But more on that soon.

As the name already suggests, War & Write II is a simple war game. What’s less obvious is how much fun can be had pushing wooden tanks and warships across the board. To explain why I enjoy this game despite being a pacifist, I have to take a step back first. Because beyond the rules and player interaction, there’s also the question of how to deal with the subject of World War II in a board game.

To start with, every play of a game can be divided into at least three layers: the interactive, the performative and the theatrical. The interactive layer covers the game’s mechanisms. When we speak of player interaction, we often equate this with how our actions directly affect other players. But interaction is better thought of as the effect our decisions have on the board state. How much of an impact does each of my decisions have on the board state, and by extension the decision space of the players involved? This is all fairly obvious and easy to identify. Drawing back to five cards in my hand at the end of every turn, affects only me. Whereas playing a card that allows me to remove one token from every other player in a contested area, has a fairly strong impact on the game state. Some rules, admittedly, go a step beyond player interaction. Communication limits, as they are commonly used in cooperative games, actually touch on the next layer I want to talk about.

The performative layer to some extent also touches on interactivity. But it isn’t build on abstract mechanisms and curated game rules. Instead we expand the game through social interaction. How we treat each other, our comments, our body language, and so-called metagaming all takes place here. The performative layer is part of the experience, but not necessarily part of the game. Do we quietly stare at the board, plotting our next move? Do we laugh, when an unexpected twist upends our plans? Do we vocally lament how bad all our options are, and that we’ve practically lost the game already? It’s gestures and actions like these, that breathe life into the experience of playing a game together. And it’s exactly these things that are often lost when we play online, unless we actively work towards reproducing them. It is the performative layer of the game that turns play into a social activity.

The last layer of the experience is “theater”. Here is where we, as players, use our creativity to expand the game’s theme. We add details and our own ideas to it. Starting with the mental image we construct, inspired by the presentation and rules of the game itself. We imagine what the application of one of the game’s rules might look like in the context of the game’s theme. It is part of “theater”, that we attempt to fuse the various player actions into one coherent whole, creating a narrative out of the events of the game. Instead of player tokens, moving across the board step by step, we speak of troop movement from Eastern Europe towards Russia, or a fleet assault on Japan. There is no immediate relation to reality, between what happens at the table or what we describe as part of theater. The components of the game don’t have a representative function, but a symbolic one. They express and idea or an image, but they do not have a direct, real life equivalent. The tiny wooden tank refers to the idea of a tank, not an actual military vehicle.

But it is also part of theater to momentarily slip into the role of the character, that the game has assigned to us. Maybe we say a few words in the way we believe the character would speak. Maybe we comment on the events of the game, as if we weren’t talking about wooden pieces or cardboard tokens, but instead actual human beings and machines. Simply put: the theater of play allows us to dip into role-playing for a moment or two. With one major difference: we make choices not based on how we think our character would act. Decisions and participation in the game and its interactions are based on our own point of view. This distinguishes board games from role-playing games (and also from acting). There we enact what we believe our character would do. In board games we do not act in service of our roles, nor do we become our roles. That is why it’s called theater. We choose our actions ourselves, but they aren’t judged on their thematic expression. Instead we evaluate them based on how other players are affected by them.

That is why the performative layer of play is rooted in our real-life reactions, whereas theater remains purely fictional. It’s a fiction we engage in for our own or each other’s entertainment. Accordingly, it is somewhat problematic to think of this part of play as “experiencing history”. This history is primarily drawn from our own imagination, making it a projection of what we already know. We don’t so much experience history, but indulge in our own prejudices, presuppositions and assumptions as part of the game. Still, this can feel so engrossing and engaging, that we can lose sight of how we had a hand in all this. It can be so thrilling, that we become convinced that the narrative lay dormant in the game all along and we have simply unearthed it. But particularly, when we care about a clean analysis of the game and the experience of playing it, it is of utmost importance we clearly separate responsibilities. The game provides us with a stage, but the theater is ours.

That is why it’s important to look at how War & Write II prepares its stage for us, and what that means for us playing on it. This starts with the game’s box, which is reminiscent of a comic book page. Its composition is very dynamic, with individual objects breaking out of their frames. The comic book-like depictions of sounds like “boom” or “bang” quickly bring to mind superhero comics. The colour palette is also bright and high contrast, further pushing away any expectations of realism. The effect is obvious: War & Write II does away with the faux seriousness and meaningfulness that other games claim for themselves. But that note carries through into the game itself. Colours are similarly bright and reminiscent of comic book art. The back of your player sheet is particularly noteworthy.

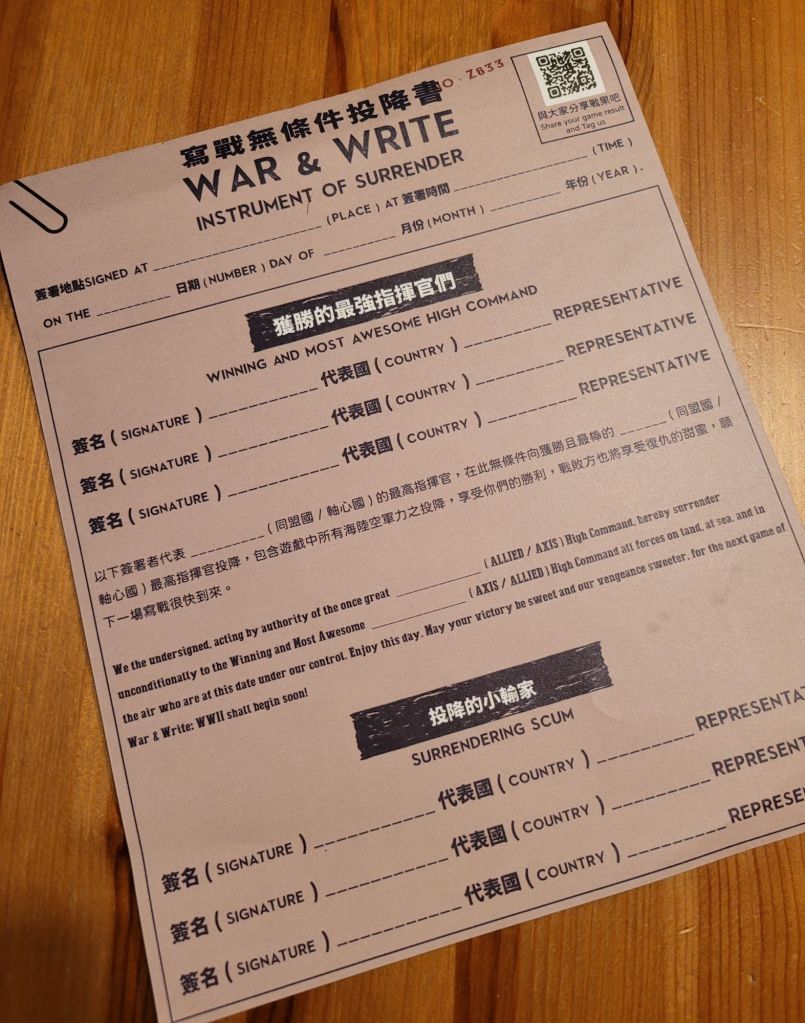

It features a pre-printed form titled “instrument of surrender” for all participating players. At the end of the game all players can write down their names and sign it as representatives of the country they played as. The winning team is named “most awesome high command”, while the defeated team has to sign under “surrendering scum”. Even within said document, there is reference to the next game of War & Write II. All of this is purely part of theater. It’s diving deep into the fiction of the game by using the means the game has provided us with. It could not be more evident that play is not about engaging real world history, or experiencing a perspective that is rooted in actual history. More than that, even within the surrender agreement the defeated players promise revenge next time. Even within the fiction, within theater, the game rejects any claim of representational value and instead refers back to the players playing a game in the real world.

By doing so War & Write II emphasizes how it functions as a board game. It centers its players and their experience and is not an approximation of historical narratives about World War II. The terms and images of the game are part of theater. They exist as part of our shared imagination and expression of the game’s events. All of which circles back to the reason we play board games: to interact with other people, to feel engrossed in a pleasant and entertaining activity or at least one that is fulfilling or emotionally compelling. War & Write II understands this, in a way that very few games like it do.