The number of reasons why people often, repeatedly and over long periods of time sit down to play a game, isn’t small. Yet to some very smart and educated folk there is a clear throughline there: to play means to indulge in escapism. To play means to retreat, at least for a little while, from reality. The controllable world of play becomes a safe haven from everyday life. It becomes a place which, with the help of a wide range of themes, we get to dress up to our heart’s desire. One such theme is nature. Whether it’s maintaining and growing an idyllic lot of land, or whether it’s protecting it from industrial exploitation. They are games in which nature is a place where we live, instead of destroying it in the unchecked pursuit of profit. In place of an ecosystem that is spiralling out of control, we seek a natural balance. One which tasks us to curate nature. We look after it and in doing so we find connections to each other. All of this is a pleasant thought, we like to return to alone or with friends. In these games we find tasks we want to take on, duties we gladly accept and characters we’re eager to interact with.

Earthborne Rangers is a game that is fully indebted to the American tradition of game design. Which is to say, that world building lies at the heart of the game and the playing of it. The most important part of the game is to create a fictional (or at least fictionalized) game world, that is coherent and can therefore be understood and imagined. Its goal is to transport players into another place and another time. Mentally and emotionally, of course. Not physically. The game is supposed to be the machine that makes this possible. Earthborne Rangers wants to spark our imagination and present us with stories, which – not unlike a book – we can get lost in. Playing intensely is close to experiencing a fantasy. We forget where and who we are. We fully identify with our characters, their challenges and feel ourselves deeply immersed in this world, far away from the actual game table.

The parallels to role-playing games are apparent. The American board game tradition is still closely related to role-playing games (and in part its precursor: the wargame). Games are understood as an interactive form of narrative. A dynamic story, which we don’t simply observe from a safe distance, but in which we can enact change. In this kind of narrative, we don’t simply turn the page, we choose the path our character will take.

It is within this understanding of board games that Earthborne Rangers exists. Accordingly it is how it should be seen and used. World building is the highest priority and the game’s design is the framework, which allows us to interact within it. The goals and incentives, which Earthborne Rangers puts before us, are the MacGuffin we’re supposed to chase after. But the experience, i.e. the immersion in this fictional world full of future nostalgia, is the reason why we’d pull Earthborne Rangers from the shelf and place it on our table.

So of course, the arguably most important question we can ask ourselves about this game becomes: what kind of world are we asked to enter? What are the ideas and values that carry this world? What’s the overarching theme that is expressed through pictures, words and conflicts in this game?

At first glance Earthborne Rangers is set in a post-apocalyptic age. Yet, the decline of the (known) world lies so far in the past, that few things still remind us of what led to that collapse. Instead of hostile wastelands, grotesque monsters and death-dealing barbarians we’re shown a flora and fauna in which people have found their place. Instead of the macabre and irony-drenched cynicism of a Fallout, we’re given an “After” that’s hopeful and almost idyllic.

The actual sense of escapism is unspoken: Earthborne Rangers is a post-capitalistic setting. It’s a world, in which the foundations of life and survival aren’t hoarded by a greedy elite, clinging to defend it at all costs, to protect their profits. It’s a world that defines itself through solidarity. A concept that some people only manage to grasp under the name “community”. Helping and supporting each other – looking past any personal quirks – is a matter of course. Our working together isn’t based on the assumption that each act will be tallied and paid back in full at some point. In other words: we don’t help others, because they might be useful to us one day, but because they are part of this world and that makes them valuable.

This idealistic thought runs through the events of the game. As “rangers” (which is what our characters are called) we act – in accordance to the world building – because we want to contribute meaningfully to society. Earthborne Rangers presents us a game world, in which we may act out of empathy. The term “cozy game” tends to often be used for shallow, low-conflict games, but seems a far more fitting description for a game like Earthborne Rangers. Because here we do have challenges, tension and even defeats, but all this happens under the guise of a game world, which promotes a positive, pleasant and hopeful vibe. It’s a game world, we like to return to, because it does feel cozy.

That was quite a few words that mostly talked about the game world and what it means for Earthborne Rangers. Which wasn’t by accident. Games in this design tradition center the game world. But what about the rules? In order to experience this game world, we need rules we can use to interact with it. What does it offer to interested players?

In a devastatingly successful act of unintended gatekeeping, trying to learn Earthborne Rangers is like snuggling with an alligator. This starts with the tutorial, which recommends that one player should familiarize themselves with the game, before leading the rest of the players through the tutorial. What sounds like an outdated joke about recursion, actually hints at an underlying problem with Earthborne Rangers’ rules.

Because even when we’ve learned how to move different tokens, card types and displays around the table, we’re no closer to understanding the actual concept of the game. You have to already know how to merge the game’s setting and rules application, to create a game world and story, in order to understand Earthborne Rangers.

Recently, only The Crew had a similar distance between rules explanation and communicating the game’s core ideas. But not only did The Crew’s sessions rarely last more than 10 minutes. Most gaming groups could also count on at least one player to have some experience with trick-taking games, which made jumping into the actual game much easier. The experienced players, which Earthborne Rangers’ tutorials recommends groups use to get started in the game, was often already seated at the table with The Crew.

Earthborne Rangers can’t really count on this. In fact, the number of players who are passingly familiar with these ideas are arguably limited to experienced players of Living Card Games like Arkham Horror or The Lord of the Rings: the Cardgame. Constructing and experiencing a game world was similarly established and explored in those games.

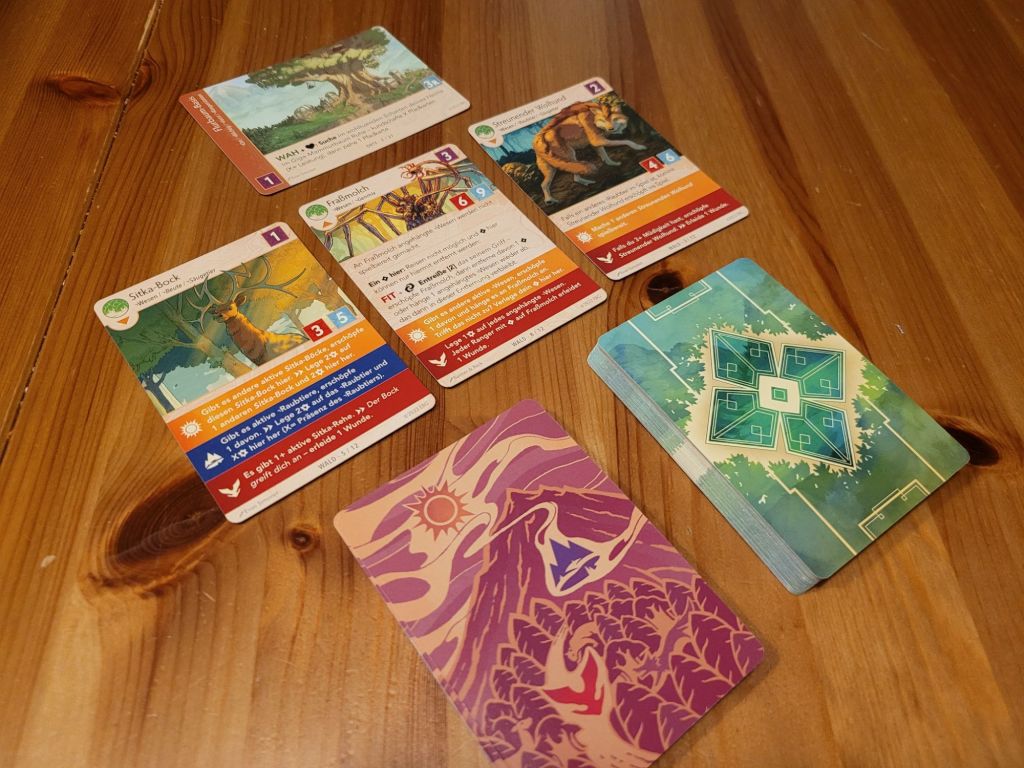

That’s why translating playing cards, flipping them over and moving tokens around to a narrated and in some sense experienced world comes easy to those players. Similarly to how puzzling, deducing and memorizing cards seems so apparent to trick-taking players, it requires no further mention. Of course, you have to do this to play the game. The difference between landscape, peoples, events and items is obvious, even if they just look like playing cards spread out across the table to the untrained eye.

If you can’t draw upon comparable experiences with other games, you will run into an invisible barrier. One that Earthborne Rangers doesn’t help you move past. The steps of abstraction that Earthborne Rangers does are difficult to follow without some practice and support. To read the events of the game as a story is noticeably easier, if there is terrain and miniatures like in Descent Legends of the Dark.

It’s noticeably more challenging to visualize what’s going on in the game world, using only some cards and their relative position to each other. That’s the narrative problem that Earthborne Rangers doesn’t quite manage to solve. Which means that Earthborne Rangers, despite its promising and commendably optimistic setting, is limited to the small group of players who have the prior knowledge to fully engage with the game.

Friends of this game might be tempted to point out, that Earthborne Rangers isn’t a family game. It’s a game aimed at experienced groups, who have experience with these games. The target demographic is experienced and veteran gamers, who know how to extract narratives from card games like these. Families and casual gamers aren’t who Earthborne Rangers is for.

And that is gatekeeping.

In light of the care that went into Earthborne Rangers’ setting to ensure that a wide range of people can imagine themselves in there, this can’t be the intended result.

Earthborne Rangers’ biggest weakness isn’t its complexity. Complex rules can be learned with enough time and effort. Its weakness is that not emphasis is placed on explaining the game’s narrative and play concept. By now there are a great number of rules videos and playthroughs to address this issue. But this only seems to show, that the game doesn’t know how to close this gap on its own.

Ultimately the question that remains is whether Earthborne Rangers is a rewarding experience for those who can make it past the entry barrier. What awaits us once we can make out the world behind these mechanisms? As mentioned above, we return to looking at the thematic underpinnings of its game world.

We are guardians of this new ecosystem, which humans have found a place in. We learn about the ins and outs of this new world as players by interacting with it. We try our hand at tasks given to us and learn from the consequences of our actions. It’s an approach that fits with a game perfectly. More than that it can be translated into a narrative.

Just as we explore the content of the game and learn from it, so do our characters grow with their challenges and the connections to other characters and events in the game world. The shared nature of playing together is echoed by the fragmented narrative texts in the provided story book. Once we manage to take these narrative impulses and cross them with our application of the rules and their thematic descriptions, we manage to create more than just a story. We unfold an entire world, if not universe, we can immerse ourselves in. Characters with whom we build friendships or rivalries. Places that can seem ominous or relaxing. Challenges that tap into our ambition or sense of responsibility.

Earthborne Rangers can be reasonably called a treasure, that we return to often, repeatedly and over an extended period of time. But as is the case with many treasures, they are hidden from the eyes of most people. Only a selected few know how to retrieve it. Which makes Earthborne Rangers into more of a myth to too many groups and turns their playthroughs of it into something like an aimless walk through the woods.