In his book „The Grashopper“ philosopher Bernard Suits wrote down an oft-quoted line: „Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.“ This quote is the kind of quip people love to throw around to seem particularly witty and cultured. As it elegantly points at the inherent absurdity of play, while also putting an emphasis on the value of effort. As if to say, yes, of course a game is only a game, but you can really sink your teeth into it. This is a short, but accurate summary of Civolution.

A slightly more expansive description of Civolution would have to mention that thematically it’s about a computer simulation of human-like civilizations. It should be noted that all explicitly historic (and anachronistic) references to various cultures in human history have been removed. While a game like Sid Meier’s Civilization or even a Through the Ages draws attention to the real places and people featured on its cards, such narrative flourishes are absent in Civolution.

This is worth pointing out, because Civolution doesn’t hold back with giving players options. In fact, the large number of unique cards, tokens and game symbols is the game’s primary unique selling point. The number of possible combinations and effects, that you can discover through the course of play, is enormous. If you were to calculate that sum and write it down, you’d probably end up with Stefan Feld’s phone number.

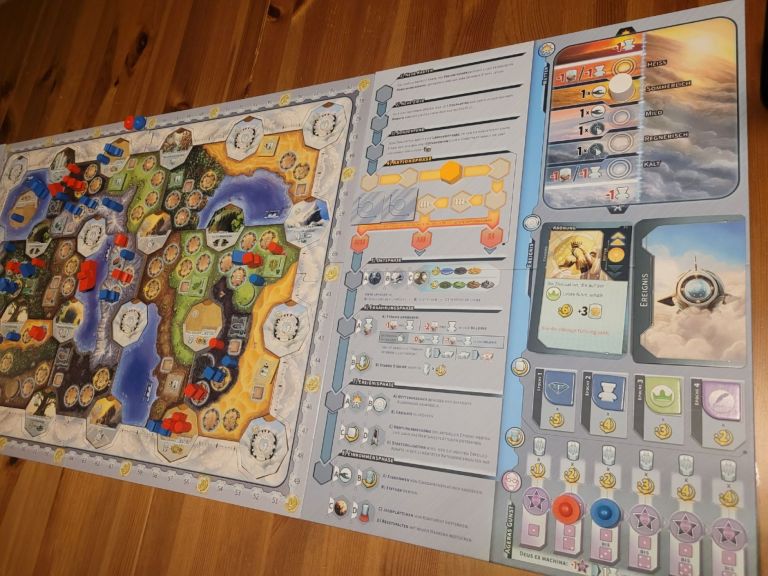

Mechanically speaking, Civolution is an impressive behemoth of a game. Your personal player tableau opens up like a book, and takes up as much space as other designer reserve for a game board for four players. You start the game with more than 20 standard actions, which can be improved and expanded upon during play. There are 15 different resources you can use and at least a dozen different sources for victory points, you will try to tap into in the most efficient way. All of them are interconnected, which is the current style. But in order to scare off the big boogeyman of this design philosophy (“What if we can math out an optimal strategy?”) all these connections are highly variable. Which means, that depending on which cards you draw, which dice results you roll and the way the shared game board is set up, you will need to adapt and fine-tune whatever strategy you wanted to pursue. In other words: with each play, you need to work out how to get the best possible result out of the countless combos available to you. To that end, Civolution offers the most important and only gamer reward there is: victory points.

This is the central tension, that Suits expressed and that Civolution exemplifies: out of the deluge of options, variable elements and even more symbols, there emerges a game that offers countless opportunities to do something. And all of it adds up feeling a bit trivial. In the end, you’ve only overcome needless obstacles, after all.

But it would be wrong to equate this with boredom. Civolution is not a boring game. Even if scoring victory points – once you take your eyes off the table for a moment – feels meaningless. Thematically, you’re pulling the strings of a civilization that’s been reduced to the efficacy of its features. But as you take on a god-like perspective in this game (as you might know from games like Populous, Sid Meier’s Civilization, etc.) your puppet civilization seems faceless. Its achievements and performance feel interchangeable. Our attempt to influence the game’s outcome is more about optimizing our decision tree than it is about playing a game.

After I shared my first impressions of the game, I was asked what kind of expectations I had going into it. To which I bluntly answered “more game, less admin”. This meant, of course, that I fell victim to the classic game critic blunder: looking for fun in the decisions I get to make. This approach is valid for some games, but not for all. Some games feed off of the haggling and negotiating that happens above the table. Some need a bit of theater as we act our assigned character roles and pontificate using our role’s language. Yet other games are simply a visual and tactile feast, that lets us imagine having wild adventures in its world. In Civolution, though, admin is part of the experience. It is, arguably, a significant part of why you would want to play Civolution again.

Just like a 5000 piece jigsaw puzzle doesn’t appeal because you’re reconstructing a beautiful or challenging image. At some point, sorting the pieces, arranging them systematically and following a strict plan to find just the right piece, is deeply intertwined with the joy we get from looking at the finished picture. It is this effort, that makes Civolution appealing. Handling 20 actions, 16 special abilities and 12 victory point sources isn’t a nuisance in the game’s design, but the necessary prerequisite for a full experience. It is this wealth of options and the effort it takes to handle them, that makes Civolution feel epic. Correctly executing actions and procedures, applying our internalized rules knowledge makes us feel competent. Even though, it’s the prerequisite for a positive experience, not every game is designed to get players to that point. A surprising number of designers and publishers don’t seem to consider it their responsibility to offer help players get started. Instead they are expected to put in numerous, repeated plays in which the game gets to “reveal itself” to them.

Thankfully, Civolution doesn’t make that mistake. It’s the often and repeatedly commended work of Viktor Kobilke that allows players to get into the fun of actually playing Civolution, during their first game. This is the groundwork necessary to get players into the game. Once they feel confident in handling the game’s procedures, players will try out different strategies or play styles. So much of the mental work of organizing and laying out the various concepts of the game has already been done by how the components and the rulebook are designed. This is exemplary work. You can tell how effective it is, by the fact that some expert players already give the game a lower complexity rating. You can’t really brag about how easy you found it to learn this complex game, if Civolution lets almost everyone do that.

That said, at its core Civolution is a game of mental endurance. You have to continuously focus on the game and weigh your options, to make sure you’ve chosen the most effective chain of actions. This is how the game creates a quasi-flow state. It asks players to keep their focus at a certain high level throughout play. The wealth of options induce an experience that is best described as ludic tunnel vision. By doing so Civolution follows Suits’ quote. In fact, it excels in proving it. In that sense, Civolution isn’t just a game, it is the epitome of a game.

But I don’t see it that way. I find this understanding of game and play both reductive and superficial. Of course, there are obstacles in games. Of course, overcoming these obstacles is one way of describing the act of play. But the passion that some games can evoke can’t simply be explained away with getting to solve some arbitrary task. I’d like to believe that gamers aren’t solely driven by performing mental feats for victory point treats. I think that games offer more than optimizing moves and comparing victory points at the end.

This is where Civolution, despite its wealth of components and the meticulous pre-sorting of all the rules and limitations, ends up stumbling. Because despite our god-like rule over an entire civilization and its adaptation to its surroundings, little remains outside of the experience of having put serious effort into playing it. There are no surprising twists and no dramatic climax. Every risk you take, only endangers the efficiency of your next turn or the ease with which to resolve it. Every setback results in a slightly less productive turn or slightly fewer victory points. The emotional depth of Civolution is quite manageable. The design doesn’t dare tie your decisions to meaningful, let alone frustrating, consequences.

Even if we look beyond how mechanical intricacies impact our experience, the civilizations we guide, feel intangible. They are little more than extensions of the mechanisms themselves. It’s difficult to see them as their own thing, and by extension as an expression of a coherent idea or theme. Some games confront you with the inevitability of losing accomplishments. Other games celebrate capitalist myths. At best, Civolution orbits around its own mechanisms. It only ever highlights how they impact one another and how it results in a sum of victory point.

But this also doesn’t necessarily have to be a negative. A game can simply be about executing its rules. Most roll’n’write games work this way and leave a positive impression. Many smaller trick-taking games are just a puzzle made up of the restrictions spelled out by their rules. It doesn’t take some highfalutin “artistic expression”, to create a sufficiently satisfying play experience. But all these games are also purposefully compact. Every rule and option that isn’t absolutely necessary has been removed. The point of developing and editing these games was to make them as complex as necessary, and as simple as possible. Civolution has pointedly done the opposite.

Civolution’s volume is its most pronounced feature. Everything it offers to players, it does so in bulk. This results in massive stack of rules, a large table presence and hard to minimize game length. But a maximalist approach to game design like this one, has to be justified in some way. Why should players choose to spend time tackling this colossus of a game? Why does the game need this wide range of different actions? How does gameplay benefit from adding so many variables to its rules framework? I have the sneaking suspicion that nobody asked Stefan Feld these questions, and Civolution continued to grow in size as a result. But this turns many aspects of the game into an end in themselves. The reason why Civolution is a big game, is because it can be. The reason why it takes a lot effort to play, is so that players can put a lot of effort into playing it. You choose to play Civolution not because it’s easy, but because it’s hard.

Still, you can tell the amount of effort and care that went into making every part of the game. It’s hard not to be impressed by this. Actions, resources, dice manipulation, exploration, expansion, upgrades and upkeep. Soon you’re drawn into this swirl of elaborate plans and ever-expanding calculations. The elegance with which you go from clueless neophyte to strategic mastermind gets all too quickly dismissed as simplistic game design. But it’s a credit to everyone involved in the creation of this game that it is so easy to purposefully and productively use the rules, you’ve only just learned. It can be incredibly motivating to learn something, apply this knowledge right away and immediately reap the benefits. But at the end of the day, the resulting experience is just scaling up a victory point track.

The emotional center of the game is not above the table or in the presence of other players, but in the calculations and plans playing out inside your head. Civolution’s thematic framework – the final exam in a civilization academy – only serves to heighten our distance to the events of the game, instead of making our actions more tangible and easy to imagine. This means that an important driver making play more engaging has been severely neglected. Once the game is over it’s always possible to read some narrative connection into the various cards in your personal tableau, or to conjure up images of why your civilization invented beer brewing before developing agriculture. But by then, it’s too late. An engaging experience has to happen during play, not when you’re re-telling play.

Playing Civolution is defined by the effort you put into situation analysis and action forecasting. What can I do right now, and what do I want to do in the next few turns? We put all our energy into moving within the limits of the rules, and draw most of our positive feedback out of staying competitive within those limitations. If you’re playing games to overcome obstacles you’re faced with using the specifically selected means you’re given, you’ll quickly find your rhythm with this game.

Civolution is a game of diligence. This is probably the highest praise and most cutting criticism, that can be leveled at it.

One thought on “Game Night Verdicts #110 – Civolution”