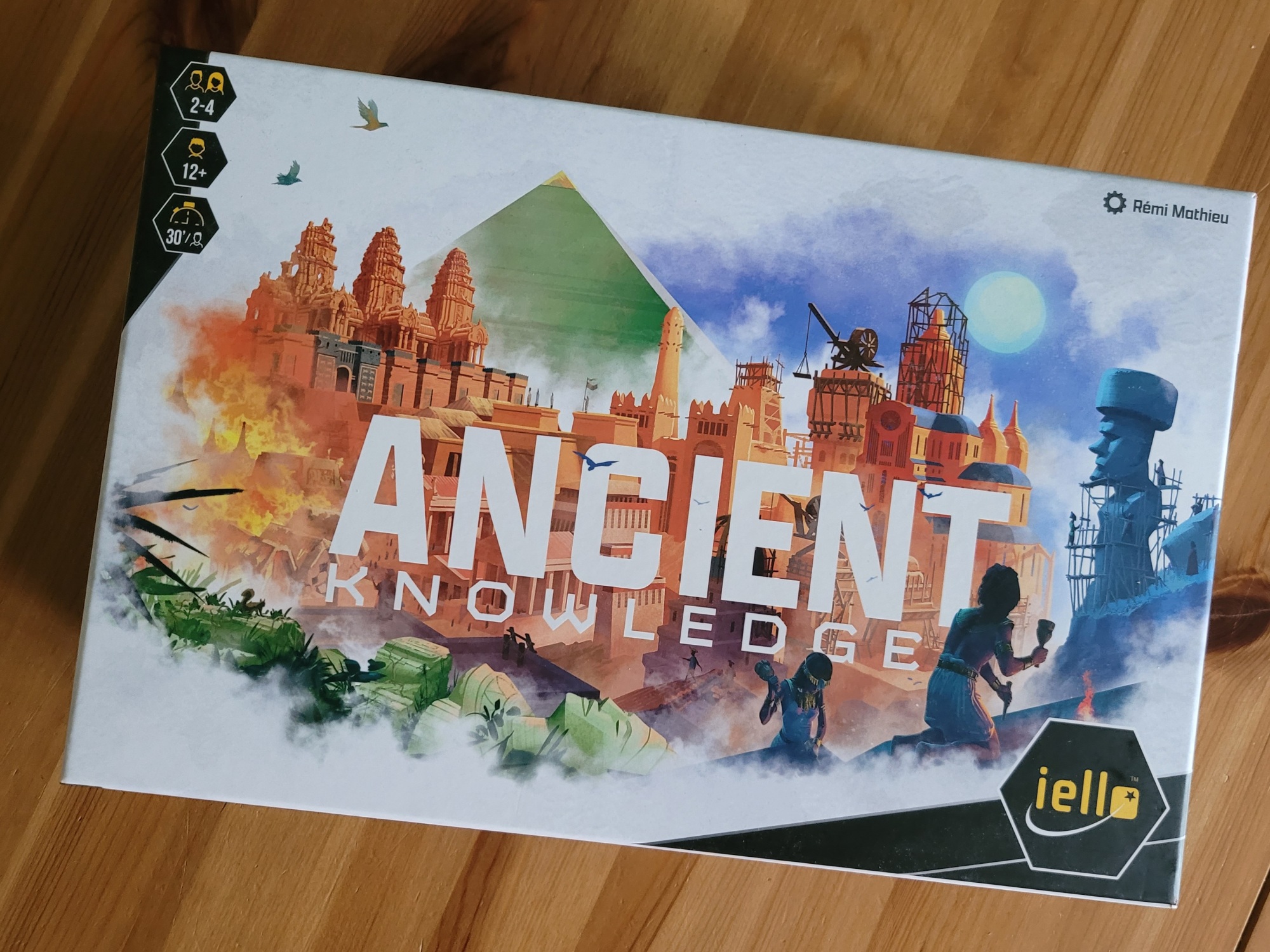

Calling something a trend can have an air of dismissiveness to it. As if a trend is just a temporary slump in board game tastes, that will soon be forgotten about. But trends are usually pretty good in tracing how design craft and tastes change over time. Our understanding of modern design tropes is shaped by trends, put in motion by single games. Agricola popularized the worker placement mechanism. Dominion brought the concept of deck building to a wider audience. Games that build on those design ideas obviously constitute a trend. Something similar is happening right now, even though it isn’t centered on a single mechanism. Instead it’s a feature of individual games which becomes the driving force behind the overall experience: the card tower.

It takes up to six rounds

to turn cards into

victory points

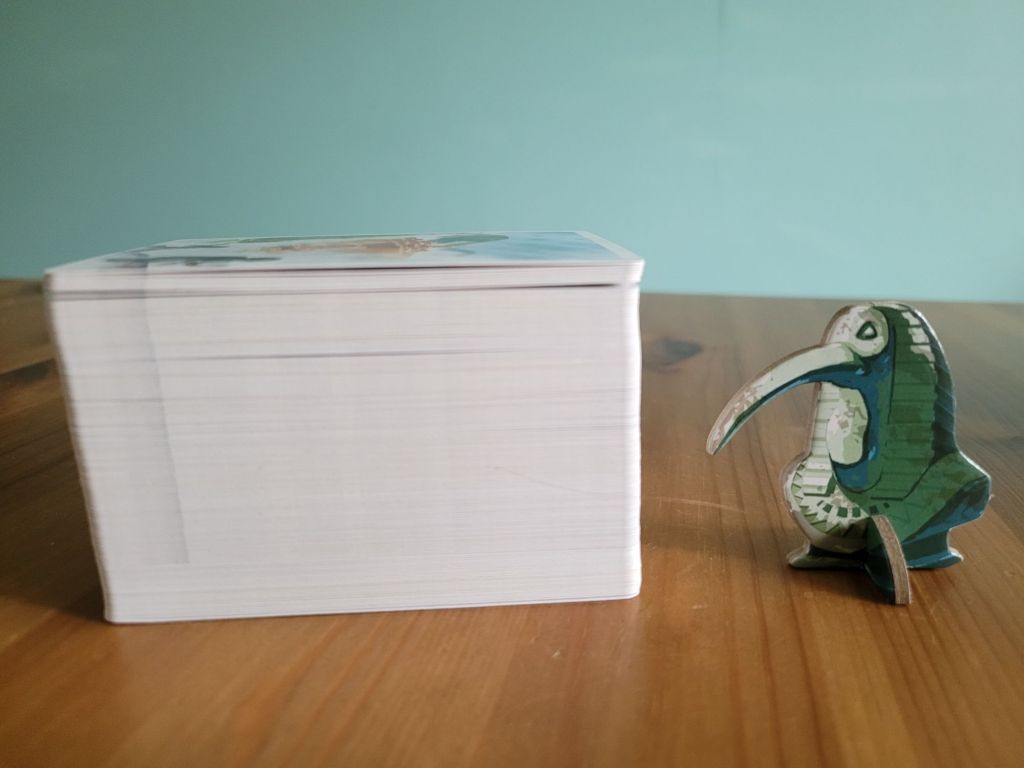

With usually far more than 100 cards the card tower is significantly bigger than a regular deck of cards. But it isn’t just the amount that matters here. It’s also the fact that the card tower consists solely of individual cards with clearly distinct gameplay effects (i.e. additional rules) on each. Choosing and applying them cleverly is what playing such a game is all about. Each time you play, there is the unspoken promise of discovering new combinations and new strategies. Long term appeal – it is assumed – is a result of the desire to try out all those combos, or to at least see them in action. But with that design approach comes a risk. It takes quite a bit of time and effort to feel confident enough in the game, to play it fluidly. If you play to win and are ambitious enough, you will have to put in the time to analyse all available card effects and evaluate their cost-benefit ratio for your current game. The first few plays of such a game tend to be anything but quick and easy-going. Experienced gamers are used to this kind of rocky start with a new game. In fact, it’s considered to be particularly rewarding for gaming groups, who like to play a game over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over and over again.

A lot of what defines Ancient Knowledge is based on the assumption, that you belong to one of those groups. More than 140 individual cards wait to be discovered and used. There is an enormous amount of rules overhead to consider each turn. Accordingly, the densely printed rulebook barely mentions any background information and leaves only a little more space for examples.

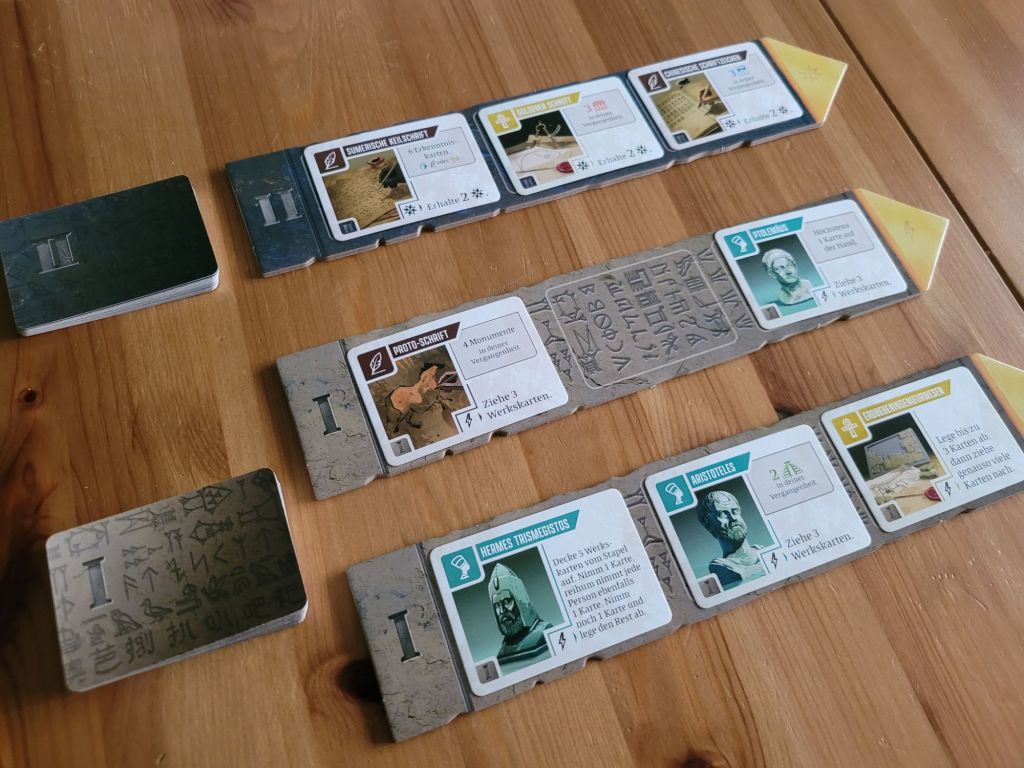

The game’s core idea is quickly summed up. Play cards from your hand above your personal game board. Each turn your cards move one step to the left, until they are moved past the board. The cards themselves have a point value that’s added up at the end of the game. They also carry tokens, which reduce your point total. With the help of various card effects, you’re trying to remove those tokens while simultaneously hurrying the cards along your board. This structure features numerous decision points throughout, so the number of rules you have to consider during your turn, quickly increases. Your board and the cards feature various symbols, you have to understand and take into consideration. There are rules text on each card you have to observe and apply at the right time. On your turn you get to choose twice from a set of five distinct actions, in order to move through the sea of short rules texts on the table. These actions are given reasonably expressive names, but they do not help to deduce the corresponding rule from it.

Smaller cards add

some more rules text

to keep on top of

Because Ancient Knowledge is, to its core, a game about rules. It’s the rules we’re playing with, not the other players. The rules set is both tool box and opponent in one. The game’s theme remains an afterthought. It does, at least, not contribute as much as it could. You get the impression that “ageing civilization” only served as inspiration and vague concept guideline for the game. During its development and completion, it was delegated to just visual packaging. It led to some pleasant illustrations on the cards, but is of negligible relevance to the experience itself.

That’s regrettable, because it’s a missed opportunity to enrich the game as a whole. Not because it should have spend more time abstracting how civilizations dealt with monuments and knowledge into its rules. That’s the realm of didactic games and sometimes wargames. In a board game, theme is its own facet of the experience. It can enrich our imagination and help give weight to our decisions. Theme offers narrative colour to help us uphold the magic circle at the table. The oft-invoked sense of “immersion” can be traced back to how a game’s theme fires up our imagination. This can be done by simulating important interactions through rules. But sometimes it’s enough for it to provide a narrative expression to our actions.

Ancient Knowledge doesn’t pursue this idea. Players’ attention is focused on walking through each step in turn order, carefully laid out in the rulebook. The moments of tension in this game are a result of being overwhelmed by too many conflicting incentives. You need to plan for card effects, coordinate them and try to efficiently collect victory points.

The large number of cards (the previously mentioned card tower) offers an excess of options, which are usually staggered over multiple rounds. This makes Ancient Knowledge feel as if it is continuously in motion. Both the row of cards, that moves one step to the left each round, as well as the wealth of factors and effects, you have to keep in mind, are in constant flux. After a few games, you get the impression that Ancient Knowledge is a game with a strong racing character. But it’s only with more experience, that you can start to develop strategies that will actually hasten the end of the game.

Card tower (without expansion)

has outgrown

the start player standee

A lot of what makes Ancient Knowledge interesting and appealing only reveals itself after a few plays. Not because the game is particularly weak or boring at first (it isn’t), but because a lot of the knowledge you need to play well is obscured at first. An example: cards come in three colour-coded groups. There are cities (red), megaliths (blue) and pyramids (green). It’s only when you compare cards of each colour group with each other, you start to pick up on mechanical similarities. One colour type amplifies cards of the same colour. Another manipulates the game’s flow. The third serves to counterbalance other card effects. Ancient Knowledge quietly assumes that gamers will engage in this kind of system analysis on their own. Neither the rulebook, nor the game’s components suggests this kind of connection between cards. Ideally, this kind of design analysis is seen as a rewarding task, as opposed to tedious homework.

Ancient Knowledge presents itself as a game about preserving knowledge. At the same time a lot of what players need to know to play well, is hidden within the game’s components. Only through repeated play do we unearth this information. Admittedly, this thematic resonance did make me chuckle. But unlike the insights gained from ancient Sumerian stone tablets or South-American artefacts, the things we uncover here don’t feel like important anthropological finds but more like a collection of tax loopholes. I can imagine this makes accountants and insurance salespeople get hot under the collar. But if you don’t belong to either of those groups, you will find Ancient Knowledge will keep you occupied, but not excited. It’s something that Ancient Knowledge shares with many games of this card tower trend.