Word association games are an abstract affair. Players are expected to think in general categories and vague contexts. The trick in those games is often found in how they make use of the unique etymological features of a language. Just take a single word and swap one context for an entirely different one. It’s these kinds of semantic leaps, that makes these games feel special.

You’re just thinking about “cast” like in a movie or a play, and then suddenly you’re talking about shadows or even a broken arm. These kinds of light-bulb moments feel like little victories, that are already hinting at a successful resolution of the game. Most of all, they’re far more memorable than the game’s outcome itself.

Accordingly the most prominent examples of this genre are very thin thematically speaking. Games like Codenames or So Clover offer few thematic hooks. Their experience is based on abstract thought patterns. There is no fiction to enrich the experience.

By comparison, Landmarks tries hard to offer some kind of coherent theme. One to four (or even 10 in the team variant) players are stranded on an island. They’re looking for treasure and try to evade traps, without actually knowing where those things are hidden. One person has a small map in front of them, but may only communicate through single word clues written on hexagonal tiles, which the stranded party places on the board adjacent to any previous placed tiles. This is how they will be guided past any dangers and towards treasure. But the guide is not allowed to use directions like north, south-west etc. Because then there would be no game.

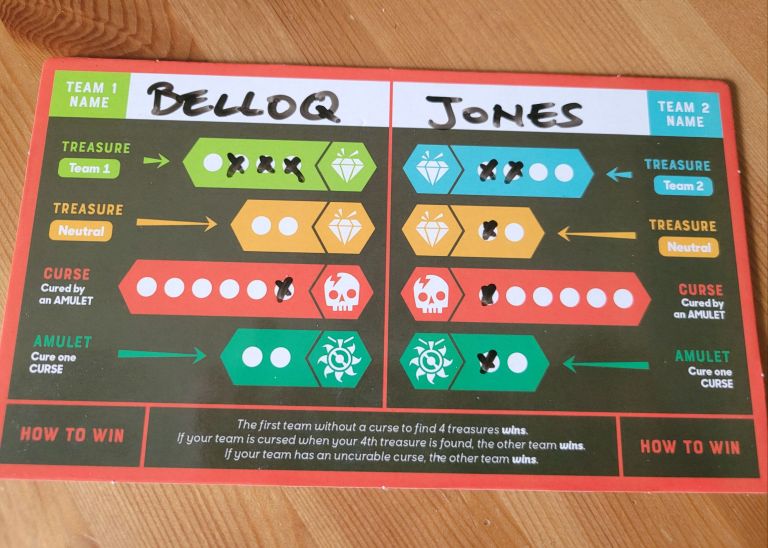

The cooperative variant of Landmarks – much like Precognition – is the advanced level of the game. For inexperienced gamers, the significantly simpler competitive version works as a decent tutorial. Two teams – each with their own guide – compete to get to four treasures first. The island board (or cloth map) is shared by both, so each word placed, offers new options to the other team but also new words to associate with their given tile with.

Do you help your own team or will you unintentionally set things up for the other team? This is vaguely reminiscent of Decrypto. Although Landmarks benefits from a far easier to grasp concept and structure. That’s why playing Landmarks competitively feels much closer to Codenames. Each placement of a new word tile results in ether helping your own team, helping the opposing team or even damaging your team. The game’s flow is familiar. It works well and plays easily. The added topological element is the kind of miniscule gimmick, that you can use to convince yourself that both games deserve a spot on your shelf.

The cooperative variant of the game offers a more intriguing challenge. Instead of competing vying for victory against another team, you have step up your efforts to get to the finish line. The added rules mechanism – the number of word tiles is limited and has to be replenished regularly – make it vital for you to have a plan in mind when you start to play. When you give hints, you need to anticipate all the ways the team might misread your clue. The team on the other hand needs to keep in mind what their next goal might be. Pure logical deduction based on the word clue is only half the battle. You can’t play without the thrill of making a gut decision.

That said, cooperative Landmarks suffers from putting a lot of responsibility on the clue giver. Based on the map they’re given, they have to come up with a plan for the whole game and adjust it continuously based on the decisions of their team-mates. If you find it uncomfortable to have success and failure of the entire table be based on your decisions, you will not enjoy being the clue-giver here. By comparison, the team has an easier job. They simply have to decide, based on the tiniest linguistic nuance and interpretation on which of two seemingly equal sides of a tile the new word clue should be placed. “Red” obviously goes next to “cherry”. But should it also connect to “lava” or maybe “sauce”?

It’s in these moments that Landmarks reveals it’s rather challenging nature. The clue-giver has to consider these kinds of decisions in their strategy. Landmarks isn’t a simply word association game. It is actually a communication game making use of a word association mechanism, with the goal of getting your team safely off the island.

That’s why the thematic hooks aren’t optional and basically irrelevant. They exist to make the task tangible to its players. One person picks a route for the others and leads them along, using only single-word clues. We imagine ourselves listening to a broken radio that only drops single words, which we have to decode to hopefully leave this dangerous with some treasures in our hands. This isn’t about immersing ourselves in some fictional scenario. It’s about turning the game’s task into something easy to imagine.

Word association games are abstract, because their mechanisms are purely abstract. Landmarks isn’t the kind of game that represents a situation or simulates a scenario. It offers players a challenging task, that asks them to think along, to see things from the other person’s perspective and to work together. This is admittedly not a unique prospect, but it’s been competently staged here.